Drypool and Marfleet Steam Tramways

History

The Drypool and Marfleet Tramway was the brainchild of four Hull businessmen, who saw the need to connect the newly built Alexandra Docks, which opened on the 20th July 1885, with the centre of Hull. Their collective vision was for a tramway that would carry thousands of workers from the town centre out to the docks located along the north bank of the Humber, and to the settlement of Marfleet to the east. Unfortunately, access to the centre of town — over the tracks of the Hull Street Tramways Company — never materialised, whilst the eastern terminus never progressed beyond Alexandra Dock, making it the shortest steam tramway in the British Isles, at a mere 1.34 miles.

The promoters consulted extensively with Hull Borough Council, ensuring that all its requirements would be met, and that there would be no municipal objections to its parliamentary bill. The Drypool and Marfleet Steam Tramways Company was duly formed on the 15th January 1886, powers to build and operate the tramway being granted on the 25th September 1886 under the Drypool and Marfleet Steam Tramways Order, which was passed into law by the Tramways Orders Confirmation (No. 2) Act, 1886. As originally envisaged, the tramway was to run from two termini on the east bank of the River Hull (the main one near North Bridge in Witham and the other opposite Drypool Bridge in Clarence Street), the lines joining at the junction of Clarence Street and Hedon Road, before heading eastwards along Hedon Road, out past Alexandra Docks, and over the Holderness Drain to Marfleet, in total 2.6 miles. Unfortunately, share take-up fell short of expectations, possibly due to concerns over the tramway's earning potential, the countryside beyond Alexandra Docks being sparsely populated, coupled with the significant financial contribution that the company would have to make towards the widening of the bridge over Holderness Drain.

As a result, construction of the tramway did not start until the 2nd July 1888, which forced the company to twice seek an extension to the time allowed for construction, the original date having been one year from the enabling act's Royal Assent, i.e., the 25th September 1887. The line finally opened on the 22nd May 1889, services initially being provided by four Thomas Green and Sons steam engines and five G F Milnes-built trailers, with three more engines and trailers arriving by December. The line was, however, only opened as far as Lee Smith Street, just beyond the depot (in Hotham Street), which was at the western end of Alexandra Docks. The rest of the line was never completed, the company repeatedly applying for extensions to the time allowed for construction, but eventually throwing in the towel in 1892.

All was not well at the other end of the line too, the extremely flat terrain enabling wagonettes to ply between the centre of town and the docks with relatively ease. The vehicles ran straight through, whereas passengers for the steam tramway either had to walk to Witham or Drypool Bridge, or else take a Hull Street Tramways Company horse tram to Witham then change to a steam tram. As a consequence, the steam trams repeatedly operated at a loss, which the company attempted to remedy by taking over the HSTCo's Holderness Road line. Although powers to purchase the line were obtained on the 4th August 1890 under the the Drypool and Marfleet Steam Tramways Order, which was passed into law via the Tramways Orders Confirmation (No. 1) Act, 1890, the deal failed, in part due to objections to the use of steam traction in the city centre.

Having been blocked from running into the city to the west, and being unable to raise the money necessary to expand to the east, the outlook for the D&MSTCo was fairly bleak, the company subsequently seeking powers to sell the steam tramway to either the corporation or the HSTCo, and at the same time formally abandoning its powers for the unbuilt portion of the tramway out to Marfleet. Although these powers were granted on the 27th June 1892 by the Dryfleet and Marpool Steam Tramways Order, which was passed into law by the Tramways Orders Confirmation Act, 1892, nothing more transpired, so the company was left to operate the tramway as best it could.

The tramway had, however, been well built, and relatively cheaply, so with careful management, combined with some modest loans, the company was able to survive through to 1894/5, when a general upturn in dock trade saw revenue finally exceed expenditure, though at the cost of reduced services and the withdrawal of the services along Clarence Street. Although welcome, the surpluses were small and were immediately swallowed up by interest payments on the loans, so the tramway never in fact made a profit, nor did it ever pay a dividend.

The long-suffering shareholders eventually found salvation in the form of Hull Corporation, which by late 1896 was running its own tramway, having taken over the assets of the Hull Street Tramways Company from the liquidator in late 1896. The corporation's energies were first and foremost focused on converting its newly acquired horse tramway to electric traction, as well as significantly extending the system, so it was not until after the first electric service commenced on the 5th July 1899, that agreement was reached with the D&MSTCo to purchase the steam tramway. The company continued to run the steam trams until the formal handover took place on the 31st January 1900, whereupon the existing staff were transferred to the corporation, with everything essentially continuing as before. The corporation obtained powers to electrify and extend the line on the 6th August 1900 via the Hull Corporation Tramways Order, which was passed into law under the the Tramways Orders Confirmation (No. 3) Act, 1900. With electrification imminent, the corporation naturally minimised expenditure on the engines, which by January 1901 had dwindled to just two operational vehicles; as these were insufficient to provide a public service, the trams were promptly withdrawn, the last service running on the 13th January 1901.

Uniforms

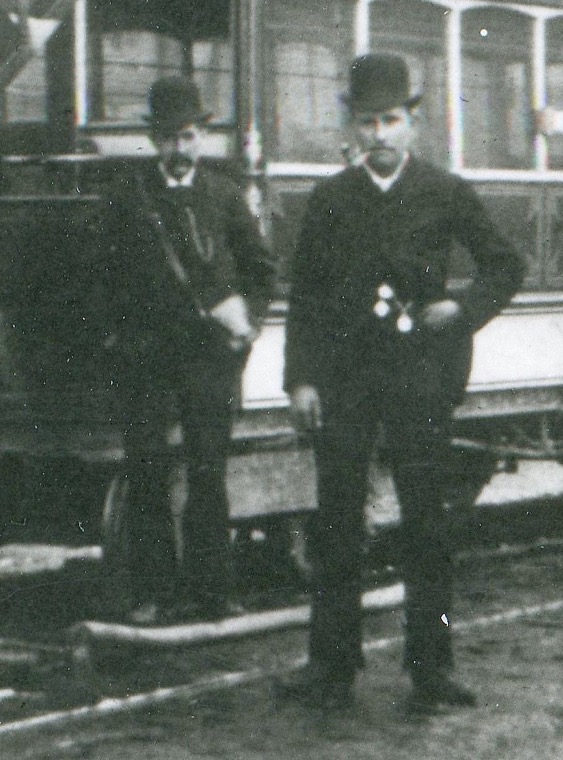

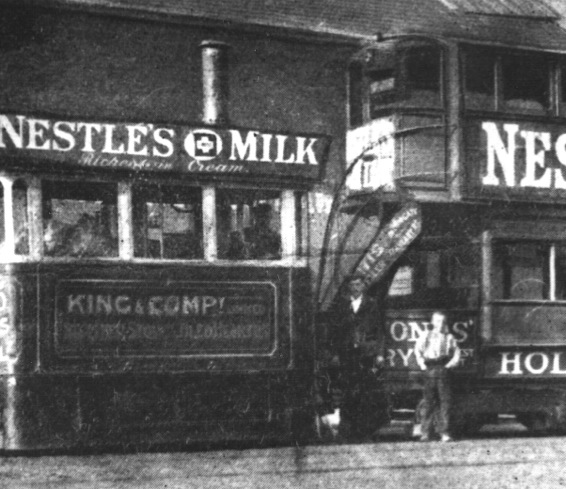

Photographs of employees of the Drypool and Marfleet Steam Tramways Company, either in company or in corporation days, are relatively rare, however, those that have survived clearly show that uniforms were not worn, neither were licence badges. Drivers wore the same clothing as their counterparts on other steam tramways, namely, railway footplate-like attire: cotton jackets and trousers, and heavy cotton caps. Conductors on the other hand wore smart but informal attire: jackets, trousers, shirts and ties, along with the fashionable headgear of the day, initially the tall bowlers of the late 1880s, and towards the end of the system's life, flat caps.

In December 1892, the company employed 12 drivers and 12 conductors, though their numbers were subsequently reduced to 8 and 9, respectively, as part of the company's cost saving efforts.

Further reading

For more information on this tramway, see: 'A History of Kingston Upon Hull's Tramways' by Malcolm Wells; Adam Gordon Publishing (2012).

Images

Steam tram drivers and conductors

What looks to be a fairly new No 6 (a Thomas Green & Sons product of 1889) and its pristine G F Milnes-built, top-covered trailer, suggesting that the photo was taken soon after the former's delivery in December 1889.

An enlargement of the above photograph showing the driver, in typical cotton jacket and cap, both devoid of badges.

Another blow-up of the above photograph, this time showing the conductor (left). He is wearing informal attire and a tall bowler hat, a style that was particularly prevalent in the late 1880s. No badges or licences are in evidence.

A Drypool and Marfleet Steam Tramways Company steam tram (purportedly No 7) and trailer — photo undated, but certainly taken no earlier than 1896 when advertising boards were introduced, and probably much later. The conductor, assuming he is the figure standing between the engine and the trailer, is wearing informal attire and a flat cap. With thanks to the National Tramway Museum.