Glasgow Tramway and Omnibus Company

History

The Glasgow Tramway and Omnibus Company Limited, which was incorporated on the 13th September 1871, had an unusual genesis, being the result of an amalgamation between two tramway schemes that had been forced together by Glasgow Corporation. The latter had steadfastly opposed all tramway development within the city, but with the impending Tramways Act of 1870, suddenly found itself faced with two schemes that might well succeed. The corporation's worst nightmare — a tramway operating in its streets, outside of its direct control, and worst of all, for commercial gain — was to be avoided at all costs, so it quickly reached agreement with the two sets of promoters for the schemes to be combined, provided that a clause was inserted into the legislation enabling the corporation to take over the resulting powers within six months of them being granted, should it so choose. The promoters were apparently induced to sign-up to this in exchange for the corporation dropping all its objections, and an agreement that the latter would lease operation of the tramway to a new company (the GT&OCo) that the promoters would subsequently form.

Powers to build the system were granted on the 10th August 1870 under the Glasgow Street Tramways Act, 1870, the corporation subsequently exercising its right to take over the powers within the stipulated time frame. Prior to the formation of the GT&OCo, the corporation summarily set the period of the lease to 23 years, to run from the 1st July 1871; this seems particularly bizarre given that no lessee company existed (officially), and construction had yet to start, let alone a tram appear in revenue-earning service.

The promoters behind the scheme were closely connected to the British and Foreign Tramways Company, which had its fingers in many tramway schemes around the world, and from whom significant investment could be expected. The GT&OCo was in effect a subsidiary of the B&FTCo, the latter duly buying up all the omnibus operators in Glasgow on its subsidiary's behalf, thus clearing the way for the tramway to make the best possible start, untroubled by competing modes of transport.

Construction commenced on the 22nd September 1871, the first tracks being laid to standard gauge; however, a decision was soon taken to change the gauge to 4ft 7¾ins to permit the running of railway wagons over the system, the initial tracks having to be regauged. The first line to open — St Georges Cross to Eglinton — commenced operation on the 19th August 1872.

The corporation managed to maintain control of all tramway lines within the city by repeating the approach it took with the GT&OCo, namely, inserting clauses into two tramway schemes that were largely outside the city, but which had some stretches within it. Powers for these two schemes were granted under the Vale of Clyde Tramways Act, 1871 (on the 13th July), and the Glasgow, Bothwell, Hamilton and Wishaw Tramways Act, 1872 (on the 10th August), after which the corporation duly took over and constructed the portions of the schemes that lay within the city, subsequently leasing them to the GT&OCo. The company commenced operations over the newly built section that the corporation had taken over from the Vale of Clyde Tramways Company on the 17th December 1872, followed by the full line (as the lessee of the VofCTCo) on the 1st January 1873; the latter was operated until around the 1st July 1874, after which the VofCTCo took over itself.

Although more corporation lines gradually followed, progress was glacially slow, the last of the first tranche of lines not opening until the 29th June 1876, with the corporation stubbornly building lines from the periphery to the centre, and ignoring the company's pleas to construct the crucial connecting lines in the centre that would enable it to operate the system efficiently and profitably. The company was by now struggling, as not only was it prevented from operating what were expected to be the most lucrative services, but it had also become apparent that the terms of the lease were simply too onerous, having been heavily weighted in favour of the corporation. If things had started badly for the company, they were only set to get worse, and though it would eventually turn out to be a profitable undertaking, it would be at loggerheads with the corporation for well over twenty years, the corporation going out of its way to make the company's life as difficult as possible.

Powers for further corporation lines were obtained on 19th July 1875 under the Glasgow Corporation Tramways Act, 1875, which also confirmed the lease arrangements made with the GT&OCo. The company was however only willing to take on the operation of additional lines if the terms of the lease were altered, as it was unable to make the undertaking pay under the current terms. After much political manoeuvring, and protracted negotiations, an agreement was finally struck in 1879, the same year that yet more new lines were authorised (on the 3rd July 1879) under the Glasgow Corporation Tramways Act, 1879.

In the meantime, the company had managed to gain independence from its parent company, which since the 27th April 1874 had been reconstituted as the Tramways Union Company Limited, the directors of the GT&OCo announcing the buy out on the 18th February 1878.

A second tranche of lines was opened between the 20th March 1880 and the 1st September 1882, by which time the GT&OCo's horse tram fleet was hovering around the 200 mark, the company constantly rebuilding and replacing its older vehicles. Yet more powers for new lines were obtained on the 19th May 1884 and the 6th August 1885, under the Glasgow Corporation Act, 1884, and the Glasgow Corporation Tramways Act, 1885, respectively.

A third tranche of lines opened between the 14th March 1886 and the 6th April 1888, which bar some minor remodelling, took the corporation horse tramway system to its final size of circa 30.40 miles. The system comprised a series of lines radiating out from the centre of the city, with a fairly dense network of interconnecting lines within the latter. The lines reached Whiteinch in the west; the Botanic Gardens and Maryhill in the northwest; St Georges Cross in the north; Springburn in the northeast; Whitevale and Dennistoun in the east; Bridgeton Cross in the southeast; and Queenspark and Govanhill in the south.

On the 7th December 1889, with the end of the lease in sight, the corporation released the terms that it expected to be met for a renewal of the lease. The terms were so stringent that no company could possibly operate profitably under them, leaving little doubt that the corporation did not want the company, or indeed any company, to operate the system beyond 1894. This was despite the fact that local authorities were, at that time, not allowed to operate tramways themselves. The GT&OCo's situation became absolutely clear three months later on the 6th March 1890 when the council formally decided that the lease would not be extended. This had fairly predictable consequences, in that the company stopped all unnecessary expenditure, including rebuilding and renewals, the tramcar fleet thereafter becoming increasing dilapidated.

The corporation quickly obtained powers to operate the system using mechanical power (on the 28th July 1891) — under the Glasgow Corporation Act, 1891 — following these (on the 24th August 1893) with powers to construct a significant number of additional lines, under the Glasgow Corporation Act, 1893.

The company eventually decided to offer the tramway side of its operation to the corporation, but as it would not agree to refrain from using its omnibuses to compete with the tramcar services, the council turned the offer down flat on the 22nd December 1891.

The mileage operated by the GT&OCo expanded further in the early 1890s when it took over operation of Glasgow and Ibrox Tramways (on the 28th May 1891) and the Vale of Clyde Tramways Govan lines (on the 10th July 1893), both of which had been bought by the corporation's neighbouring authority, the Govan Police Commissioners. For a few short years, company cars therefore extended beyond Paisley Toll, southwestwards along Paisley Road to just beyond Whitefield Road, and westwards along Govan Road to Linthouse.

The poor state of relations between the company and the corporation, and the sheer levels of municipal obduracy, are perfectly illustrated by the latter's decision not to buy any of the company's trams, horses or depots, and to buy all these new, a titanic waste of ratepayers' money. The company for its part, then built a whole new fleet of omnibuses to compete with the corporation tramway.

The corporation duly took over operation on the 1st July 1894, but with only circa 40% of the vehicles necessary, which was no doubt much to the financial benefit of the company. The latter's joy was, however, short lived, the corporation gradually outcompeting the company with more trams and cut-price fares. Seeing which way the wind was blowing, the company sold its lease of the Govan lines to the corporation, running its last tram service of all on the 10th November 1896.

The company struggled on for a few more years (as an omnibus operator) but finally threw in the towel on the 20th May 1902, when it decided to voluntarily wind up its affairs. Overall, and despite the constant battles with the corporation, the company had been very profitable, paying half-year dividends of 3-6% between December 1875 and December 1879, hovering around 9-11% between December 1880 and December 1887, before hitting a peak of 12% in December 1888, then falling to 5% between June 1892 and June 1894.

Uniforms

Photographs of GT&OCo staff reveal that conductors were issued with single-breasted, calf-length coats, with five buttons (almost certainly brass and bearing the GT&OCo monogram — see link) and lapels. Caps were in a kepi style, and appear not to have carried a cap badge; certainly, none can be seen in photos, and none have ever come to light.

In common with many UK horse tramway operators, drivers were left to decide on their own attire, often turning out in heavy-duty jackets with bowler hats (the headwear of choice for most horse bus and tram drivers during this era). Both drivers and conductors wore a round municipal licence, usually hung from a button or cash-bag strap; drivers' licences were black on white enamel, whilst those issued to conductors were black on yellow enamel (see below).

Photographs of GT&OCo inspectors appear not to have survived, and the company may even not have employed them, though given the size of the system, this does seem somewhat unlikely

Further reading

For a detailed history of the GT&OCo, see: 'The Glasgow Horse Tramways' by Struan Jno T Robertson; Scottish Tramway and Transport Society (2000).

Images

Horse tram drivers and conductors

GT&OCo Horsecar No 439 — photo undated, but probably taken in the 1880s. Photo courtesy of the Tramways and Light Railway Society, with thanks to David Voice.

An enlargement of the above photograph showing the driver, who is in informal attire, and the conductor, who is wearing a single-breasted uniform jacket with a licence badge and kepi-style cap.

Driver licence badges, 1st and 2nd Class — white enamel with black lettering. It is believe that trams were designated as 1st-class vehicles, so horse-tram drivers would have worn 1st-class licence badges. There are presumably no 2nd-class conductor badges as conductors only worked on 1st-class vehicles.

Conductor licence badge — yellow enamel with black lettering.

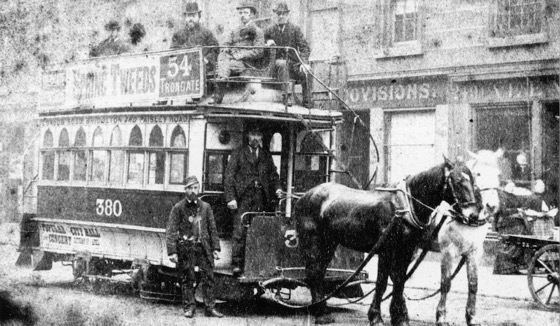

A rather decrepit Horsecar No 380, with crew, taken in 1888. Photo courtesy of the Tramways and Light Railway Society, with thanks to David Voice.

An enlargement of the above photograph showing the conductor, again in a single-breasted jacket with a kepi-style cap (nonchalantly worn to one side) and with a licence badge hanging from a coat button. Although the photograph is of poor quality, it does seem to suggest that the kepi-style caps did not carry a badge of any kind.

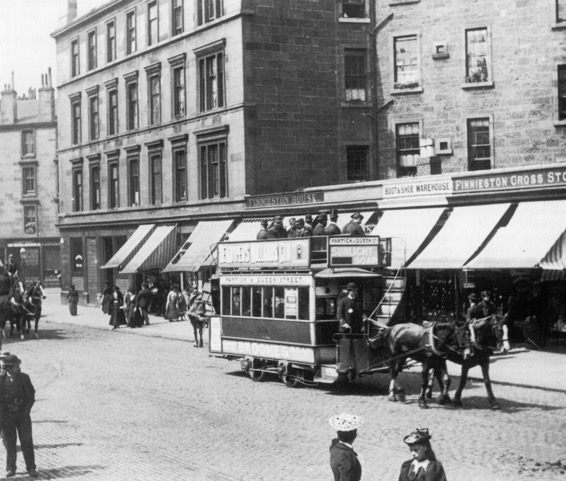

GT&OCo Horsecar No 254 at Finnieston Cross — photo undated, but probably taken in the 1880s. Photo courtesy of the Tramways and Light Railway Society, with thanks to David Voice.

An enlargement of the above photograph showing the driver, who is clearly wearing informal but smart attire, along with a bowler hat and a municipal licence badge.