City of Oxford and District Tramways

History

The 33-year history of Oxford's horse-drawn tramway system is one of repeated disagreement and dispute between the owning company and the corporation, within the corporation/council itself, and between the council and the public (ratepayers, academics and powerful individuals). The entire city seems to have swung between acknowledging the necessity and desirability of a tramway within its environs, to not wanting a tramway under any circumstances. Whilst there was much grumbling during the first two decades of operation, this reached a whole new level as the prospect of electrification hove into view, particularly in respect of the potential disfigurement that would be caused by overhead electric wires.

The first promoters to obtain powers for a horse tramway in the city — under the Oxford Tramways Order of 1879 — planned a more extensive system than was eventually built. As soon as the powers were confirmed (on the 11th August 1879 under the Tramways Orders Confirmation Act 1879), they set about the task, registering a company to raise the finance (the Oxford Tramways Company) on the 20th November 1879, and signing a construction contract the same day! Although the promoters must have had some level of corporation buy-in in order for the bill to be passed, it seems that the finer details were still to be agreed. Unfortunately, discussions with the corporation dragged on and on, primarily focused on aesthetic considerations, a subject that would dog the tramway throughout its existence. After a year of haggling, the company threw in the towel, and handed over to a new company — The City of Oxford and District Tramways Company — which was formed on the 14th December 1880.

The new company endeavoured to work more closely with the corporation from the off, revising the scheme to shorten the mileage and reduce the amount of double track. Construction of the first line began on the 24th May 1881; it ran from the railway stations on Botley Road (owned by the London & North Western Railway Company and the Great Western Railway Company), eastwards through Carfax and along High Street, then over Magdalen Bridge to the eastern terminus on Cowley Road near to its junction with Leopold Street. The line was built to a gauge of 4ft, and was opened on the 1st December 1881. The second line opened on the 28th January 1882; this ran northwards from Carfax along Magdalen Street and Banbury Road to Rackham Lane (now St Margarets Road).

Provisional orders for extensions were acquired on the 2nd August 1883 and the 25th September 1886 under the Oxford Tramways (Extensions) Orders of 1883 and 1886; these were passed into law via the Tramways Orders Confirmation (No. 3) Act 1883 and the Tramways Orders Confirmation (No. 2) Act 1886. The first of these new lines branched off from the Banbury Road line at Magdelen Street, then ran northwestwards via Walton Street to a terminus on Kingston Road (opened 15th July 1884); the second line ran southwards from Carfax along Abingdon Road to a terminus at New Hinksey (opened 15th March 1887).

Although the relationship between the company and the corporation was occasionally less than harmonious, with one disagreement over payment towards the widening of Magdalen Bridge ending up in court (the company lost), by 1896 the tramway was carrying circa 3 million passengers a year, so it was certainly a successful concern.

A further extension order was granted on the 2nd August 1898 by the Oxford Tramways (Extensions) Order 1898, which was passed into law under the umbrella of the Tramways Orders Confirmation (No. 3) Act 1898. The investment, however, was only made following the corporation's agreement to postpone its right to buy the tramway (under the 21-year rule enshrined in the Tramways Act of 1870) from 1900 to the 31st December 1907. The new extension ran northwards from the old Rackham Lane terminus to Summertown, the new terminus being opposite South Parade; this was opened on the 5th November 1898, and took the horse tramway to its final extent of 5.25 miles.

The new track was laid to electric tramway standards, the company clearly believing that it would be able to convince the corporation to allow it to convert the tramway to electric traction. Proposals duly followed in 1902, the company requesting a rather optimistic 40-year lease in exchange for the investment it would need to make. The corporation rejected the proposals, not least because it had its own aspirations for a municipally operated electric tramway. Agreement was, however, eventually reached with the company (on the 6th September 1905) for the corporation to acquire the tramway on the 31st December 1906, leaving it ample time to obtain the necessary powers. The corporation was, though, in for a nasty surprise, as the scheme was a costly one, and it had clearly not reckoned with the views of its ratepayers. The council lost on a show of hands at a public meeting called to discuss the scheme, and followed this up with another defeat in a poll it had insisted upon after the first reverse.

Nevertheless, the council still wasn't ready to give up, even though it was fairly clear that a municipally financed scheme was unacceptable to the ratepayers; it therefore invited tenders for the conversion, the successful bid — from the National Electric Construction Company being accepted on the 6th December 1906. The NECCo subsequently registered a subsidiary — City of Oxford Electric Tramways Limited — to convert and operate the system. Rather than buying the existing tramway and retaining it, the corporation decided that things would be altogether smoother if they obtained powers to convert the tramway, and at the same time vested the old tramway in the new company. This approach was almost certainly performed to head off civic objections to the corporation owning the tramway (and the costs that would involve), but one which would still allow it a high degree of control over the tramway, not to mention the receipt of an annual rent for the concession.

Powers to electrify the tramway were duly obtained by the corporation on the 21st August 1907 under the Oxford and District Tramways Act, 1907, these then being handed over to the company. The council's intention was to use the Dolter surface-contact system in aesthetically sensitive parts of the city (to avoid unsightly overhead wires); however, a visit to Hastings to see the system in action failed to instil the City engineer with confidence, the council unanimously rejecting it at a meeting on the 30th December 1907.

The old tramway company continued to operate the horse tramway beyond the 31st December 1907 due to disagreements over the valuation, the new company only taking over in March 1908. After due reflection, the company proposed a new scheme, primarily using overhead current collection, but with conduit rather than surface-contact current collection; conduit was, however, extremely expensive to install, the only major user being London County Council Tramways. The corporation agreed to the new scheme, the company subsequently obtaining powers for the redesigned system on the 16th August 1909 under the Oxford and District Tramways Act 1909, .

However, after jumping through hoops to try to find a solution, the company seemingly got cold feet, coming up with various excuses for not starting the project. This was almost certainly down to cost, as the company eventually suggested, probably more in hope than expectation, that it would perhaps be able to find the money after all, provided that overhead current collection could be used throughout. Needless to say, the proposal was rejected, as were various later proposals (in 1912), one for petrol-electric trams, which though it found favour with the council, was subsequently rejected at a public meeting on the 9th July 1913.

The company then gave up on the conversion, instead offering to hand over the tramway and to replace the services with motorbuses. However, before the corporation had time to fully consider how it wished to proceed, motorbus competition appeared on the streets — on the 5th December 1913 — in the form of the Oxford Motor Omnibus Company, which used a system of tokens to avoid breaking the law, the council having so far refused the company (or indeed anyone) a bus-operating licence. The public quickly deserted the trams in their droves, sending a very clear signal to the council. Licences to operate motorbuses were finally issued to a number of applicants, including the tramway company, on the 7th January 1914, initially for a three-month experimental period.

An agreement was then reached between the corporation, the NECCo and the CofOETL on the 22nd May 1914 for the tramway to be transferred to the corporation, which would then remove it, and for the companies to be given licences to run replacement omnibuses; the agreement was confirmed on the 7th August 1914 by the Oxford and District Tramways Act 1914.

The last horse tram duly ran some time in August 1914 (the exact date has not been recorded).

Uniforms

Although surviving photographs are not of the highest quality, they clearly show that up until the mid-Edwardian era, conductors and drivers simply wore informal attire: trousers, jackets, waistcoats, shirts and ties. Headgear appears to have followed the fashion of the day, predominantly the bowler hat, though this gradually gave way to the flat cap as the years wore on. No badges of any kind were worn on either the jackets or the hats.

In the years leading up to the end of the City of Oxford and District Tramways Company's tenure (circa 1905-1908), photographs show conductors wearing smarter jackets than hitherto, though without metal buttons, strongly suggesting that they were not formal issues (probably bought by the employees from the same supplier). There was, however, a change in headwear, several photographs showing some conductors (though not all), wearing tensioned-crown (top) peaked caps; these caps appear to have borne a prominent cap badge, possibly of metal. Details of the cap badge, however, remain unknown, as no examples appear to have survived.

From the early 1890s (it is unclear when), tramcar crews were required to wear round enamel licence badges (possibly of the type depicted below), though these appear to have eventually fallen out of use if the surviving photographs are anything to go by.

It is currently unclear what uniforms if any, inspectors wore.

My thanks to John Perkin for the background information.

Further reading

For a history of the system, see: 'The Tramways of Oxford' by H J H Wheare, in the Tramway Review Nos 140 (p103-116), 142 (p176-195) and 143 (p213-223); Light Rail Transit Association (1989 and 1990).

Images

Horse tram drivers and conductors

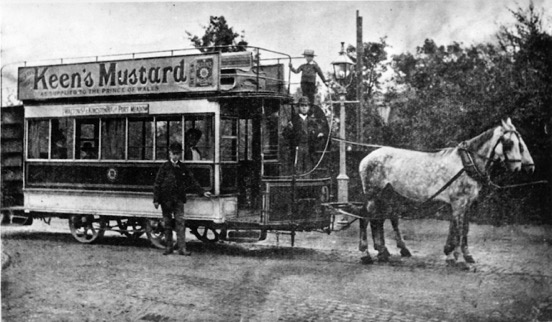

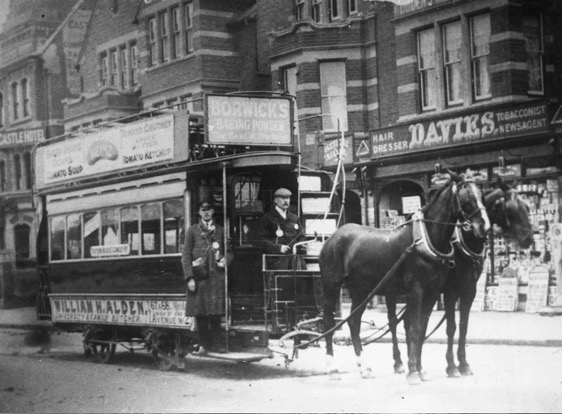

A conductor and a driver with double-deck Horsecar No 9 at the Kingston Road terminus — photo undated, but probably taken in the late 1880s. Photo courtesy of the Tramways and Light Railway Society, with thanks to David Voice.

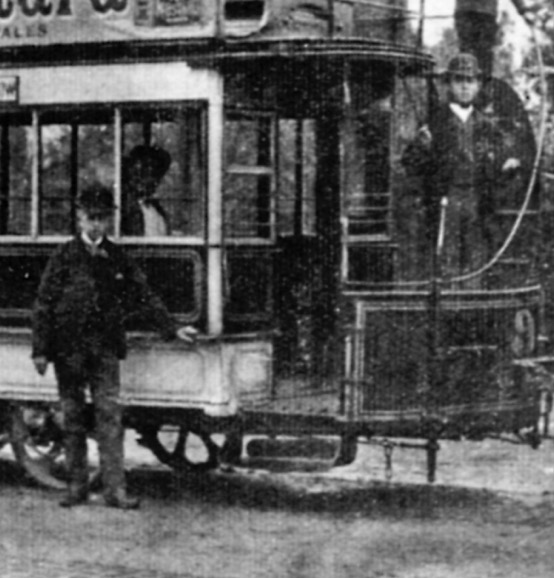

An enlargement of the above photograph showing the crew, both of whom are wearing informal attire. Neither man is wearing a municipal licence badge.

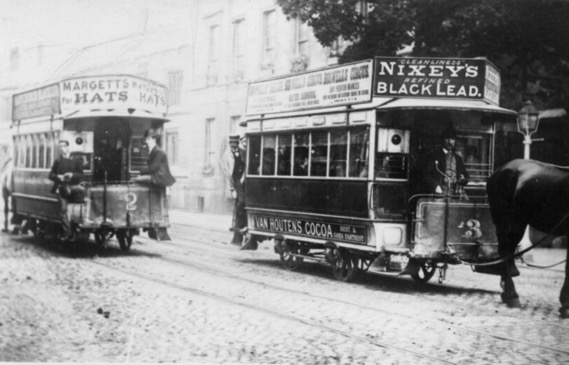

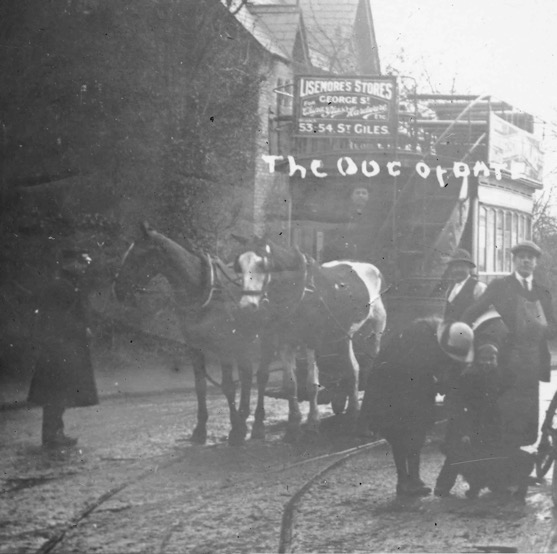

Single-deck Tramcars No 2 and No 3 pass in the High Street — photo taken circa 1891. None of those present appear to be wearing licence badges or uniforms. Photo courtesy of the Tramways and Light Railway Society, with thanks to David Voice.

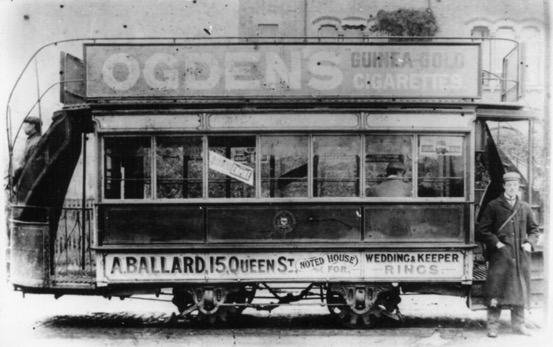

A driver and a conductor, once again in informal attire, and without licence badges, at the Cowley Road terminus — photo purportedly taken in 1901. Photo courtesy of the Tramways and Light Railway Society, with thanks to David Voice.

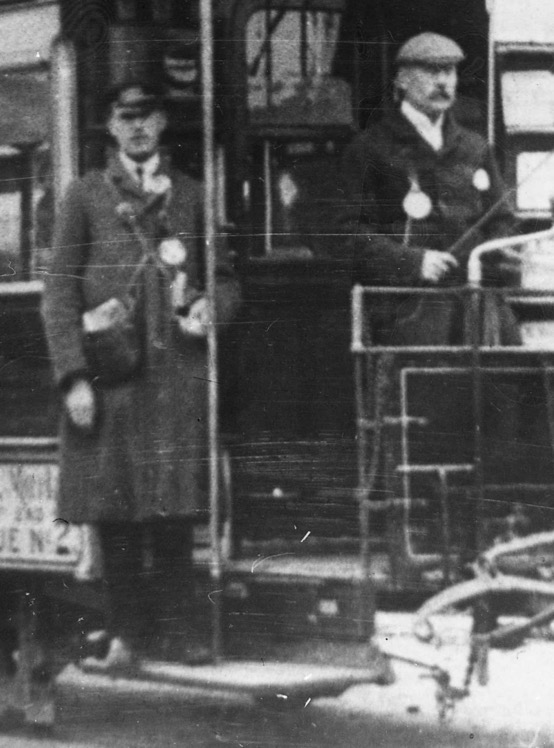

The crew of Horsecar No 18 pose for the cameraman opposite the railway stations, at what is now called Frideswide Square, in September 1906. Photo courtesy of the National Tramway Museum.

An enlargement of the above photograph, which though of poor quality, suggests that the conductor is wearing a peaked cap bearing a cap badge, Both men are also wearing municipal licence badges, possibly the same pattern as that shown below.

A possible horse-tram driver's municipal licence badge — yellow and black enamel. The Police Committee of Oxford City Council accepted a quote — on 3rd April 1890 — from the Patent Enamel Company for 300 badges for drivers and conductors at 1/- (one shilling) each (this included cab drivers), and the tram crew badges were requested to be white lettering on yellow enamel. It is therefore unclear whether the supplier did not meet the precise specification, or whether this badge is a later issue, or indeed, that it was for use by bus crews. With thanks to Nick Taylor for this information.

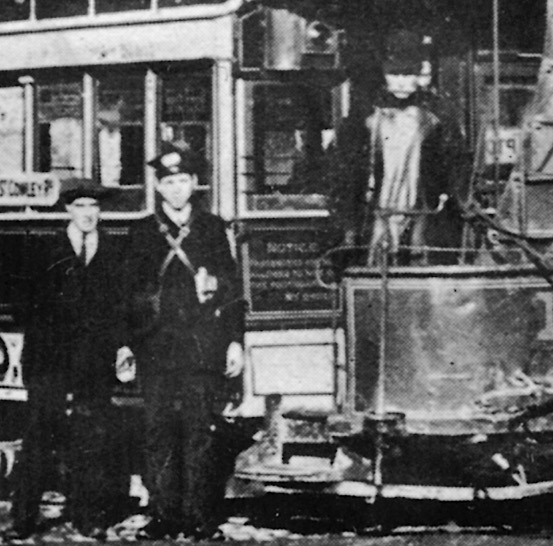

Double-deck Horsecar No 11 at the Cowley Road terminus in the penultimate year of operation, 1913. Photo courtesy of the Tramways and Light Railway Society, with thanks to David Voice.

An enlargement of the above photograph showing the driver (right), in informal attire and with a leather apron, and the conductor (centre), in an unmarked jacket, and a peaked cap that once again appears to bear a large cap badge. Neither man appears to be wearing a municipal licence badge.

A classic 'old and new' photograph, probably taken in 1914, with the old horse tram on the left and the modern motor omnibus on the right. Photo courtesy of the National Tramway Museum.

An enlargement of the above photograph showing the conductor (standing left), who is once again wearing a tensioned-crown peaked cap and a greatcoat.