Tynemouth and District Tramways

History

The Tynemouth & District Tramways began life as a horse tramway in 1880, transitioned to steam four years later, and somehow managed to survive through to electrification in 1901, despite passing through the hands of at least four separate companies and owners, two liquidations, and two closures, not including the final one for regauging and conversion to electric working!

The tramway, which was initially owned and operated by the Tynemouth and District Tramways Company Limited, opened on the 30th June 1880. The line was built to a gauge of 3ft 0ins and was initially horse drawn; it had originally been planned to run from North Shields (on the north bank of the Tyne), eastwards through Tynemouth, then northwards to Cullercoats and Whitley, a distance of around 3.5 miles. but only the stretch between North Shields (Saville St) and Tynemouth (Percy Park) was built during the horse-drawn period, a distance of circa 1.6 miles.

Despite serving a thriving fishing and industrial port (North Shields) as well as a noted destination for day trippers and excursionists (Tynemouth), the company was soon in financial difficulties. Around the end of November 1880, the directors took up an offer from a Mr Winby of Newcastle to lease the line for seven years, in return for a fixed income; they had however not reckoned with their shareholders, who refused to ratify the lease, forcing Winby to stop operations around the 17th December 1880. It seems that the company were not in a position to take-over operation, so the tramway remained closed for several weeks. Although tramway services recommenced in January 1881, the parlous financial situation meant that the company was really headed in one direction only, which inevitably ended in voluntary liquidation in the summer of 1881.

The tramway was sold at auction in London on the 30th September 1881 — by the liquidator — the new owners getting it for a fraction of what it had cost to build. The company was presumably wound up, and the new owners — a Mr Meston and a Mr Bayley — set about securing powers to extend the system, and convert it to steam traction. A short westwards extension to Prudhoe St in North Shields was opened in early 1884 with steam operation commencing some time in the spring (the exact date has not been recorded) and horse operation ceasing in April 1884.

The owners now sold the tramway to a new company — the North Shields and District Tramways Company Limited — on 23rd April 1884; this had only been registered a couple of weeks beforehand so had no capital, Meston and Bayley instead having a priority call on the money raised by future share subscriptions. Share uptake was however poor, the company resorting to debentures to partially make-up the shortfall, having to not only pay Meston and Bayley for the tramway, but also the contractors building the extension to Cullercoats and Whitley, who were none other than Meston and Bayley. Work on the extension soon stopped, and though the company struggled on, services seem to have been appallingly unreliable, expenses unsurprisingly exceeding income by a good margin; perhaps inevitability, the situation once again ended in voluntary liquidation (around August 1886).

It is unclear how long the liquidator attempted to run the tramway for, but by 1890 services had clearly not run for some considerable time. At this point, a new company appeared on the scene — the North Shields and Tynemouth District Tramways Company Limited — which had been expressly formed to take-over the assets of the old tramway company and revive the services. The tramway was purchased some time in early 1890, with services recommencing on the 12th June 1890 using overhauled engines. The tramway seems to have been better run than under previous regimes, but was still a knife-edge affair, barely being able to carry enough passengers to break even. Rescue eventually came in 1897 in the form of the British Electric Traction Company Limited, which at this time was aggressively purchasing horse and steam-operated tramways across the British Isles, with the intention of converting them to electric traction.

The BETCo usually preferred to operate its tramway interests — of which there were eventually almost 50 across the British Isles — through subsidiary companies, so the NS&TDTCo was formally reconstituted in 1899 as the Tynemouth and District Electric Traction Company Limited. Powers to convert the tramway to overhead electric traction, re-gauge it to 3ft 6ins, and abandon the steam tramway had already been acquired the previous year. The last steam trams are believed to have run in early 1900 (the precise date is unclear), when the system was closed for reconstruction and re-gauging, the first electric service running on the 18th March 1901.

An extension was opened on the 22nd April 1904, taking this small system to its final size of 4.23 miles. The tramway was essentially a long single line running from a terminus on the Tyne at New Quay, northwestwards into the centre of North Shields, before striking northeastwards and northwards — paralleling the Tyne and the North Sea coast — through Tynemouth, Cullercoats and Whitley Bay to a terminus at Whitley Bay Links. Although the tracks of the T&DETCo met those of the Tyneside Tramways and Tramroads Company at Prudhoe St in North Shields, the latter tramway was standard gauge, so no inter-running ever took place; the systems did however share a single rail (of dual-gauge track) for a short distance, a situation which was certainly unique amongst tramways in the United Kingdom.

In 1914, the T&DETCo was placed under the control of the Northern General Transport Company, which had been set up by the BETCo to consolidate its transport interests in the area; these also included the Jarrow and District Electric Traction Company Limited and the Gateshead and District Tramways Company Limited.

The tramway doubtless suffered under the many pressures of the Great War, amongst them significant staff shortages, high loadings, minimal maintenance and an inability to source new track, vehicles or spares due to government restrictions. The system probably emerged from the conflict in run-down condition (details are sparse), with a huge backlog of work, and into a post-war world of high inflation. On top of this came concerns around Tynemouth Corporation's right to buy the tramway (at various points in the 1920s) under the original enabling acts, which effectively acted as a blocker for investment. Fortunately, the company was able to negotiate a 21-year extension to the dates when the corporation could exercise its right to buy, enabling it to invest in track doubling and improvements to the tramcar fleet.

The company introduced its first bus services in June 1921, expanding them throughout the 1920s. Whilst the initial services were either tramway feeders or new routes to outlying regions, their success meant that when major expenditure was required on the tramway, a comparison would inevitably be conducted between the cost of renewing the tramway infrastructure or closing it altogether and replacing the service with buses. The death knell came in April 1930 when buses were used to provide supplementary services along the route of the tramway, it being only a matter of time before they replaced the trams altogether. The trams struggled on for another year, the last of all running on the 5th August 1931.

Uniforms

Photographs of the early horse-drawn period have not survived, so it may never be known for certain whether uniforms were issued or not, however, given that none appear to have been worn during the subsequent steam-worked era, it seems more than likely that informal attire was worn. Although surviving photographs from the steam era stem overwhelmingly from the last few years of the system's life, they clearly show that drivers wore railway footplate-like attire, primarily, heavy cotton jackets and trousers, and cloth caps; no badges were worn. Conductors wore informal attire: jackets, trousers and the fashionable headgear of the day, soft-topped caps or flat caps; in earlier years, bowler hats were no doubt much favoured, though photographic evidence is unfortunately lacking. Once again, badges or licences were not worn.

Following the take-over of the company by the BETCo in 1897, staff working the steam tram services continued to wear the same informal attire as they had under the previous owners. Staff working the new electric services (from 1901 onwards) wore the familiar and largely regulation BETCo uniform; although jackets appeared to vary somewhat between BETCo systems, as well as across the decades, the cap badges, collar designations and buttons invariably followed a standard pattern.

Photos of the early years of the electric tramway are scarce, but those which have survived show that conductors and motormen were issued with double-breasted jackets with four pairs of buttons (of the standard BETCo pattern — see link), the upper pair being mounted between the jacket lapels and collars; by analogy with other BETCo systems, the latter probably bore embroidered system initials. Caps were military in style with a tensioned crown (top) and stiff glossy peak; they bore the standard BETCo 'Magnet & Wheel' cap badge, worn above an employee number (in individual numerals). The badges and buttons were almost certainly brass. At some point, probably in the late Edwardian era, a change was made to double-breasted, 'lancer-style' tunics with five pairs of buttons (narrowing from top to bottom) and upright collars; the latter carried individual system initials on the bearer's right-hand side (’T & D T’), and an employee number on the left, all presumably brass to match the buttons. The system initials and numbers were initially striated to give a rope effect.

Inspectors wore single-breasted jackets with hidden buttons (or more likely a hook and eye affair), edged in a finer material than the main body of the jacket, and with upright collars; the latter bore Inspector on both sides in embroidered script lettering. Caps were military in style with a tensioned crown; they bore the standard ‘Magnet & Wheel’ cap badge mounted above the grade (Inspector), which was carried on a hat band in embroidered script lettering. The Chief Inspector's uniform differed only in respect of the grade, which appeared in two lines on the collars and a single line on the cap.

In common with many tramway systems, the Tynemouth and District Electric Traction Company employed female staff during the Great War to replace male employees lost to the armed services. The ladies were issued with tailored single-breasted jackets with five buttons and a waist belt (with button fastening), along with long matching skirts. The initial headgear issue appears to have been of men's caps, though these were eventually superseded by baggy caps with glossy peaks; these carried standard BETCo 'Magnet & Wheel' cap badges, though seemingly without an employee number. Female staff were also issued with long, single-breasted coats with lapels and epaulettes; the latter had a button fastening, but appear to have been otherwise devoid of insignia. Unlike the vast majority of UK tramway systems, female staff appear to have continued in employment for at least a couple of years after 1918.

Further reading

For more information on the pre-electric era, see: 'A History of the British Steam Tram - Volume 4' by David Gladwin; Adam Gordon Publishing (2008). For a short history of the electric era, see: 'The Tramways of Northumberland' by George S Hearse; self-published (1961).

Images

Steam tram drivers and conductors

A slightly battered-looking Black, Hawthorn & Co-built Steam Tram (No 2) stands with Milnes Trailer No 1 in Suez Street on an occasion which clearly necessitated the presence of various dignitaries. Given that the 'North Shields and Tynemouth District Tramways Limited' only began services in June 1890, after the system had not apparently run for some considerable time (following liquidation), the photograph may well have been taken to commemorate this event. The driver is certainly not wearing a uniform, and neither are any of the possible candidates for a conductor. Photo courtesy of David Gladwin, with thanks to Trevor Preece.

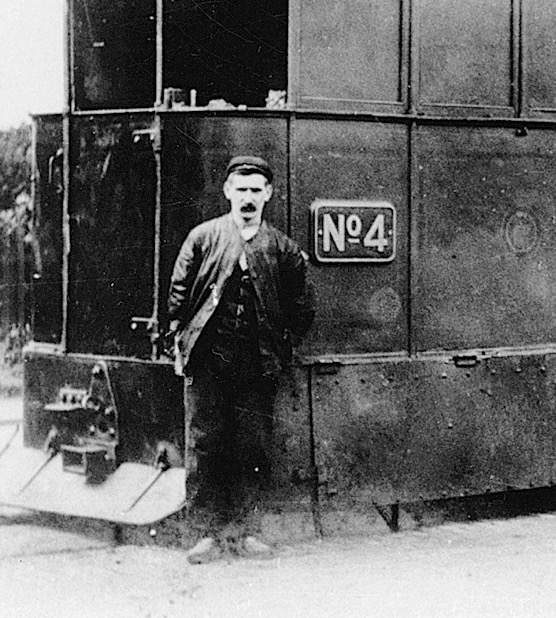

Steam Tram No 4 — a Thomas Green product — and Trailer No 5 at Percy Park, Tynemouth; the photo was taken very late in the system's life, circa 1900, when it was owned by the British Electric Traction Company. Photo courtesy of David Gladwin, with thanks to Trevor Preece.

A blow-up of the above photo showing the driver, who is wearing typical railway-footplate like attire, including a flat cap.

Another blow-up of the above photo, this time showing the rather indignant-looking conductor, again in informal attire, without insignia of any kind. The poster behind him can also be used to date the photo, as 'Tynemouth Palace' was only opened in 1898, and the system closed in 1900.

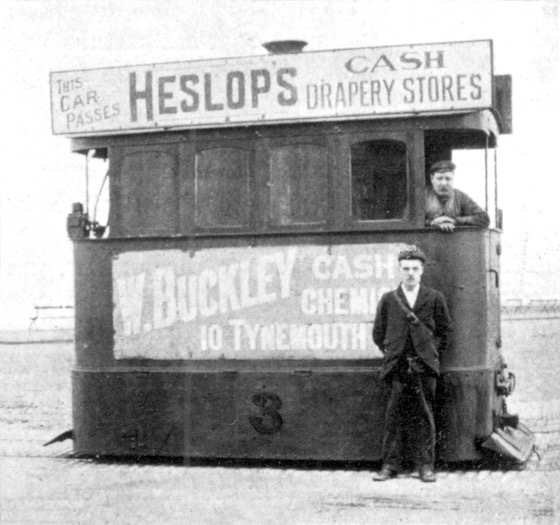

Steam Tram No 3 — a Black, Hawthorn Company product — seen very late in its life, and apparently carrying an advert which it took with it to the scrapyard, so definitely in BETCo days, and probably in 1899 or even 1900. Both men are wearing informal attire with flat caps. Photo courtesy of David Gladwin, with thanks to Trevor Preece.

Motormen and conductors

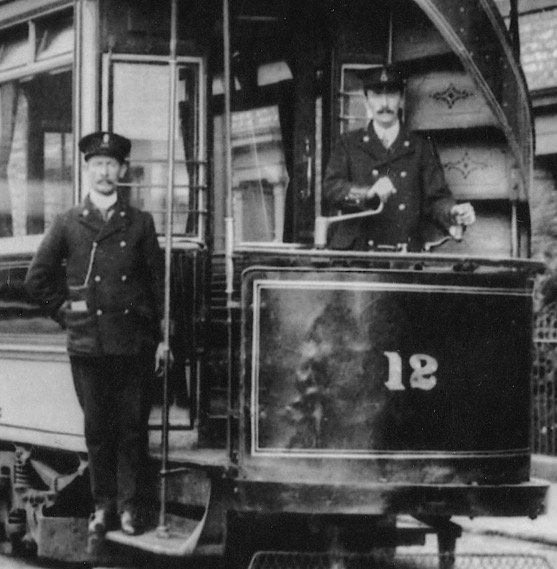

Tramcar No 12 and crew pose for the cameraman in John Street, Cullercoats — photo undated, but as the tramcar is a little battered, probably taken in the early-to-mid Edwardian era. Author's Collection.

A blow-up of the above photo showing the conductor and motorman, both of whom are wearing double-breasted jackets with lapels, and caps with the standard BETCo 'Magnet & Wheel' cap badge, above an employee number.

Standard British Electric Traction Company ‘Magnet & Wheel’ cap badge — brass. Author's Collection.

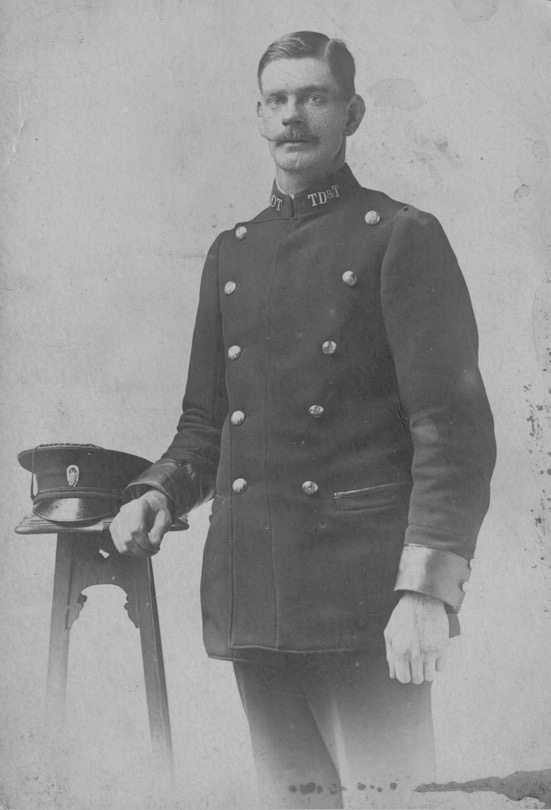

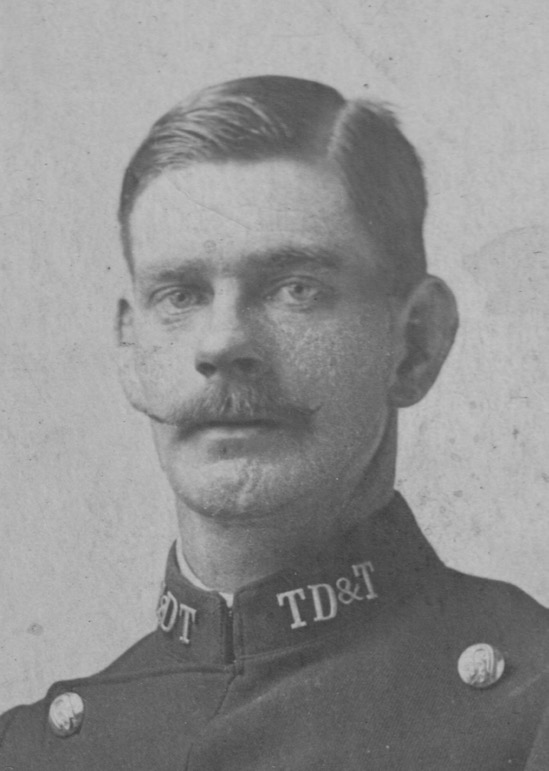

A rare studio portrait of a T&DET tramwayman — photo undated, but probably mid-to-late Edwardian. The absence of an employee number on either the cap or the collar suggests that the subject, whose name was Cyril, may have been a new employee, possibly undergoing a probationary period. The photo was taken by Burton Graham of Whitley Bay. Author's Collection.

An enlargement of the above photo showing details of the collar insignia, which are striated to give a rope effect. The initials have been inadvertently transposed; they should be 'T&DT' not 'TD&T'.

The crew of Tramcar No 3 pose for the camera in Whitley Bay in 1915. Image kindly supplied by Beamish Museum Limited (see link), image copyright Beamish Museum Limited.

A blow-up of the above photo showing the conductor and the motorman.

A conductress her motorman with Tramcar No 5 — photo taken at Whitley Bay during or just after the Great War. Author's Collection

A blow-up of the above photo showing the motorman. His cap bears the standard BETCo 'Magnet & Wheel' cap badge and an employee number (possibly either 11 or 12), whilst his right-hand collar bears individual 'T & D T' initials. Author's Collection.

A line up of various tramcar crew, depot staff and managers — photo undated, but probably taken in the early 1920s. Author's Collection.

A blow-up of the above photo showing a number of the motormen and conductors.

A conductor and motorman (Employee No 3) posing on the steps of their tramcar — date unknown, but almost certainly taken in the late 1920s or early 1930s. The conductor is not wearing an employee number on either his cap or his left-hand collar; instead, the latter bears a standard BETCo ‘Magnet & Wheel’ badge. Image kindly supplied by Beamish Museum Limited (see link), image copyright Beamish Museum Limited.

Senior staff

A blow-up of the 1920s staff photo above showing the Chief Inspector (top left) and an inspector (top right). Both men are wearing typical tramway inspector garb, differing only in the embroidered grade badges on their collars and caps.

Female staff

A blow-up of the Great War photo of Tramcar No 5 above, showing the conductress. Although her baggy cap bears a 'Magnet & Wheel' cap badge, it has no employee number. Author's Collection.

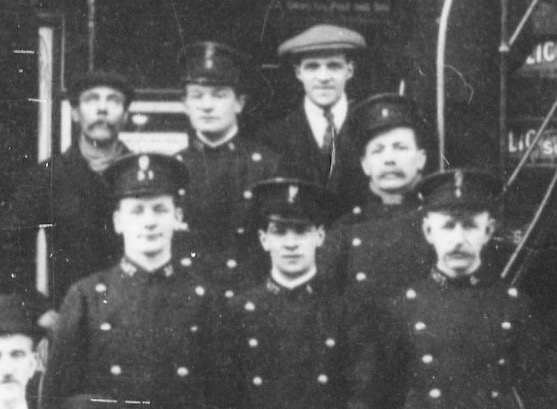

A staff photo taken at the depot at Cullercoats — photo undated, but probably taken early in 1916. Source unknown